The growing importance of global marketing is one aspect of a sweeping transformation that has profoundly affected the people and industries of many nations during the past 160 years. International trade has existed for centuries; beginning in 200 B.C. Four decades ago, the phrase global marketing did not exist. Today, businesspeople use global marketing to realize their companies’ full commercial potential. That is why, no matter whether you live in Asia, Europe, North America, or South America, you may be familiar with the brands of KFC, McDonald’s, Shell and etc. However, there is another, even more critical reason why companies need to take global marketing seriously: survival. A management team that fails to understand the importance of global marketing risks losing its domestic business to competitors with lower costs, more experience, and better products. But what is global marketing? How does it differ from “regular” marketing?

Marketing can be defined as the activity, set of institutions, and processes for creating, communicating, delivering, and exchanging offerings that have value for customers, clients, partners, and society at large.4 Marketing activities center on an organization’s efforts to satisfy customer wants and needs with products and services that offer competitive value. The marketing mix (product, price, place, and promotion) comprises a contemporary marketer’s primary tools. Marketing is a universal discipline, as applicable in Argentina as it is in Zimbabwe.

An organization that engages in global marketing focuses its resources and competencies on global market opportunities and threats. A fundamental difference between regular marketing and global marketing is the scope of activities. A company that engages in global marketing conducts important business activities outside the home-country market.

The scope issue can be conceptualized in terms of the familiar product/market matrix of growth strategies (see Slide below).

Some companies pursue a market development strategy; this involves seeking new customers by introducing existing products or services to a new market segment or to a new geographical market. Global marketing can also take the form of a diversification strategy in which a company creates new product or service offerings targeting a new segment, a new country, or a new region. Starbucks provides a good case study of a global marketer that can simultaneously execute all four of the growth strategies shown in Table 1-1 below:

Market penetration: Starbucks is building on its loyalty card and rewards program in the United States with a smartphone app that enables customers to pay for purchases electronically. The app displays a bar code that the barista can scan.

Market development: Starbucks is entering India via an alliance with the Tata Group. Phase one calls for sourcing coffee beans in India and marketing them at Starbucks stores throughout the world. The next phase will likely involve opening Starbucks outlets in Tata’s upscale Taj hotels in India.

Product development: Starbucks created a brand of instant coffee, Via, to enable its customers to enjoy coffee at the office and other locations where brewed coffee is not available. After a successful launch in the United States, Starbucks rolled out Via in Great Britain, Japan, South Korea, and several other Asian countries.

Diversification: Starbucks has launched several new ventures, including music CDs and movie production. Next up: Revamping stores so they can serve as wine bars and attract new customers in the evening.

To get some practice applying Table 1-1, create a product/market growth matrix for another global company. IKEA, LEGO, and Walt Disney are all good candidates for this type of exercise. Companies that engage in global marketing frequently encounter unique or unfamiliar features in specific countries or regions of the world. In China, for example, product counterfeiting and piracy are rampant. Companies doing business there must take extra care to protect their intellectual property and deal with “knockoffs.” In some regions of the world, bribery and corruption are deeply entrenched. A successful global marketer understands specific concepts and has a broad and deep understanding of the world’s varied business environments. He or she also must understand the strategies that, when skillfully implemented in conjunction with universal marketing fundamentals, increase the likelihood of market success.

Marketing is one of the functional areas of a business, distinct from finance and operations. Marketing can also be thought of as a set of activities and processes that, along with product design, manufacturing, and transportation logistics, comprise a firm’s value chain. Decisions at every stage, from idea conception to support after the sale, should be assessed in terms of their ability to create value for customers. For any organization operating anywhere in the world, the essence of marketing is to surpass the competition at the task of creating perceived value—that is, a superior value proposition—for customers. The value equation is a guide to this task:

Value = Benefits/Price (money, time, effort, etc.)

The marketing mix is integral to the equation because benefits are a combination of the product, the promotion, and the distribution. As a general rule, value, as the customer perceives it, can be increased in two basic ways. Markets can offer customers an improved bundle of benefits or lower prices (or both!). Marketers may strive to improve the product itself, to design new channels of distribution, to create better communications strategies, or a combination of all three. Marketers may also seek to increase value by finding ways to cut costs and prices. Nonmonetary costs are also a factor, and marketers may be able to decrease the time and effort that customers must expend to learn about or seek out the product. Companies that use price as a competitive weapon may scour the globe to ensure an ample supply of low-wage labor or access to cheap raw materials. Companies can also reduce prices if costs are low because of process efficiencies in manufacturing or because of economies of scale associated with high production volumes.

Recall the definition of a market: people or organizations that are both able and willing to buy. In order to achieve market success, a product or brand must measure up to a threshold of acceptable quality and be consistent with buyer behavior, expectations, and preferences. If a company is able to offer a combination of superior product, distribution, or promotion benefits and lower prices than the competition, it should enjoy an extremely advantageous position.

Competitive Advantages

When a company succeeds in creating more value for customers than its competitors, that company is said to enjoy competitive advantage in an industry. Competitive advantage is measured relative to rivals in a given industry. For example, your local laundromat is in a local industry; its competitors are local. In a national industry, competitors are national. In a global industry—consumer electronics, apparel, automobiles, steel, pharmaceuticals, furniture, and dozens of other sectors—the competition is, likewise, global (and, in many industries, local as well). Global marketing is essential if a company competes in a global industry or one that is globalizing. The transformation of formerly local or national industries into global ones is part of a broader economic process of globalization.

From a marketing point of view, globalization presents companies with tantalizing opportunities—and challenges—as executives decide whether to offer their products and services everywhere. At the same time, globalization presents companies with unprecedented opportunities to reconfigure themselves. Achieving competitive advantage in a global industry requires executives and managers to maintain a well-defined strategic focus. Focus is simply the concentration of attention on a core business or competence.

Global Marketing: What it is and it isn’t

The discipline of marketing is universal. It is natural, however, that marketing practices will vary from country to country for the simple reason that the countries and peoples of the world are different. These differences mean that a marketing approach that has proven successful in one country will not necessarily succeed in another country. Customer preferences, competitors, channels of distribution, and communication media may differ. An important managerial task in global marketing is learning to recognize the extent to which it is possible to extend marketing plans and programs worldwide, as well as the extent to which adaptation is required. The way a company addresses this task is a reflection of its global marketing strategy (GMS).

In single-country marketing, strategy development addresses two fundamental issues: 1) choosing a target market; and 2) developing a marketing mix. The same two issues are at the heart of a firm’s GMS, although they are viewed from a somewhat different perspective (see Table below).

Global market participation is the extent to which a company has operations in major world markets. Standardization versus adaptation is the extent to which each marketing mix element is standardized (i.e., executed the same way) or adapted (i.e., executed in different ways) in various country markets. For example, Nike recently adopted the slogan “Here I am” for its pan-European clothing advertising targeting women. The decision to drop the famous “Just do it” tagline in the region was based on research indicating that college-age women in Europe are not as competitive about sports as men are.

GMS has three additional dimensions that pertain to marketing management. First, concentration of marketing activities is the extent to which activities related to the marketing mix (e.g., promotional campaigns or pricing decisions) are performed in one or a few country locations. Coordination of marketing activities refers to the extent to which marketing activities related to the marketing mix are planned and executed interdependently around the globe. Finally, integration of competitive moves is the extent to which a firm’s competitive marketing tactics in different parts of the world are interdependent. The GMS should enhance the firm’s performance on a worldwide basis.

The decision to enter one or more particular markets outside the home country depends on a company’s resources, its managerial mind-set, and the nature of opportunities and threats. Today, most observers agree that Brazil, Russia, India, and China—four emerging markets known collectively as BRIC—represent significant growth opportunities. Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Turkey—the so-called MINTs—also hold great potential.

The issue of standardization versus adaptation in global marketing has been at the center of a long-standing controversy among both academicians and business practitioners. Much of the controversy dates back to Professor Theodore Levitt’s 1983 article in the Harvard Business Review, “The Globalization of Markets.” Levitt argued that marketers were confronted with a “homogeneous global village.” He advised organizations to develop standardized, high-quality world products and market them around the globe by using standardized advertising, pricing, and distribution. Some well-publicized failures by Parker Pen and other companies that tried to follow Levitt’s advice brought his proposals into question. The business press frequently quoted industry observers who disputed Levitt’s views. As Carl Spielvogel, chairman and CEO of the Backer Spielvogel Bates Worldwide advertising agency, told The Wall Street Journal in the late 1980s, “Theodore Levitt’s comment about the world becoming homogenized is bunk. There are about two products that lend themselves to global marketing—and one of them is Coca-Cola.”

Global marketing is the key to Coke’s worldwide success. However, that success was not based on a total standardization of marketing mix elements. For example, Coca-Cola achieved success in Japan by spending a great deal of time and money to become an insider; that is, the company built a complete local infrastructure with its sales force and vending machine operations. Coke’s success in Japan is a function of its ability to achieve global localization, being as much of an insider as a local company but still reaping the benefits that result from world-scale operations. Although the Coca-Cola Company has experienced a recent sales decline in Japan, it remains a key market that accounts for about 20 percent of total worldwide operating revenues. What does the phrase global localization really mean? In a nutshell, it means that a successful global marketer must have the ability to “think globally and act locally.”

Global marketing may include a combination of standard (e.g., the actual product itself) and nonstandard (e.g., distribution or packaging) approaches. A global product may be the same product everywhere and yet different. Global marketing requires marketers to think and act in a way that is both global and local by responding to similarities and differences in world markets. But it is important to bear in mind that “global localization” is a two-way street, and there is more to the story than “think globally, act locally.” Many companies are learning that it is equally important to think locally and act globally. In practice, this means that companies are discovering the value of leveraging innovations that occur far from headquarters and transporting them back home. For example, McDonald’s restaurants in France don’t look like McDonald’s elsewhere. Décor colors are muted, and the golden arches are displayed more subtly. After seeing the sales increases posted in France, some American franchisees began undertaking similar renovations. As Burger Business newsletter editor Scott Hume has noted, “Most of the interesting ideas of McDonald’s are coming from outside the U.S. McDonald’s is becoming a European chain with stores in the U.S.” These reverse flows of innovation are not just occurring between developed regions such as Western Europe and North America. The growing economic power of China, India, and other emerging markets means that many innovations originate there. Nestlé, Procter & Gamble, Unilever, and other consumer-products companies are learning that low-cost products with less packaging developed for low-income consumers also appeal to cost-conscious consumers in, say, Spain and Greece

The Importance of Global Marketing

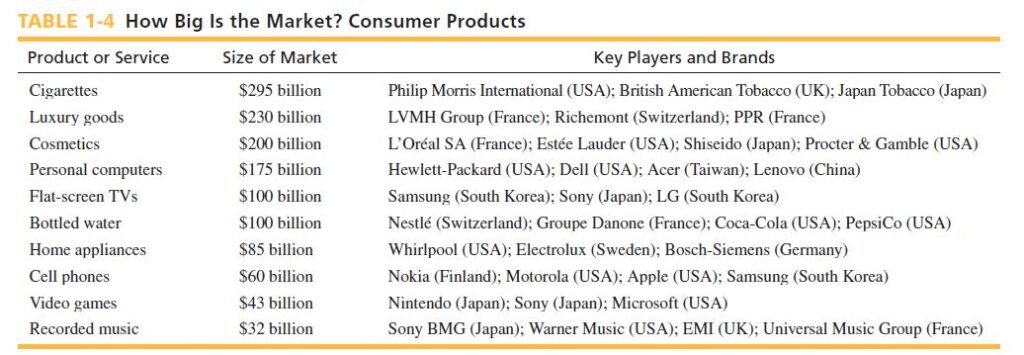

The largest single market in the world in terms of national income is the United States, representing roughly 25 percent of the total world market for all products and services. U.S. companies that wish to achieve maximum growth potential must “go global,” because 75 percent of world market potential is outside their home country. Management at Coca-Cola clearly understands this; about 75 percent of the company’s operating income and two-thirds of its operating revenue are generated outside North America. Non-U.S. companies have an even greater motivation to seek market opportunities beyond their own borders; their opportunities include the 300 million people in the United States. For example, even though the dollar value of the home market for Japanese companies is the third largest in the world (after the United States and China), the market outside Japan is 90 percent of the world potential for Japanese companies. For European countries, the picture is even more dramatic. Even though Germany is the largest single-country market in Europe, 94 percent of the world market potential for German companies is outside Germany. Many companies have recognized the importance of conducting business activities outside their home country. Industries that were essentially national in scope only a few years ago are dominated today by a handful of global companies. In most industries, the companies that will survive and prosper in the twenty-first century will be global enterprises. Some companies that fail to formulate adequate responses to the challenges and opportunities of globalization will be

absorbed by more dynamic, visionary enterprises. Others will undergo wrenching transformations and, if their efforts succeed, will emerge from the process greatly transformed. Some companies will simply disappear. Each year Fortune magazine compiles a ranking of the 500 largest service and manufacturing companies by revenues.30 Walmart, the world’s biggest retailer with more than $400 billion in annual revenues, stands atop the 2011 Global 500 rankings. Walmart currently generates only about one-third of its revenues outside the United States. However, global expansion is key to the company’s growth strategy. Oil companies occupy six of the spots in the top 10 rankings by revenues; ExxonMobil also ranked first in profitability among the Global 500. Toyota, the only global automaker in the top 10, has faced unprecedented challenges over the past few years, including quality-control issues that forced it to recall millions of vehicles. State Grid, the Chinese power company, and Japan Post Holdings, which provides mail, banking, and insurance services, round out the top 10. Examining the size of individual product markets, measured in terms of annual sales, provides another perspective on global marketing’s importance. Many of the companies identified in the Fortune rankings are key players in the global marketplace. Annual sales in select global industry sectors markets are shown in Table 1-4.

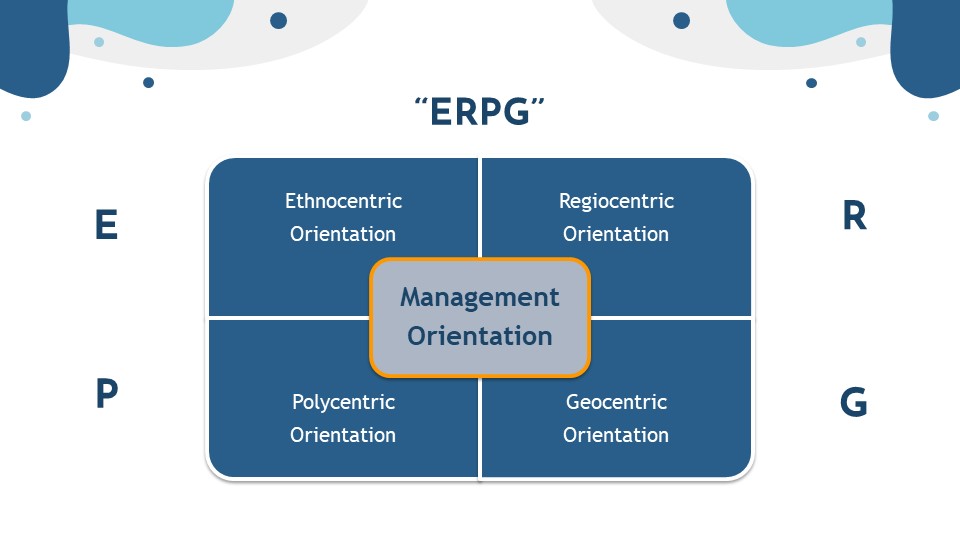

Management Orientation

The form and substance of a company’s response to global market opportunities depend greatly on management’s assumptions or beliefs—both conscious and unconscious—about the nature of the world. The worldview of a company’s personnel can be described as ethnocentric, polycentric, regiocentric, or geocentric. Management at a company with a prevailing ethnocentric orientation may consciously make a decision to move in the direction of geocentricism. The orientations are collectively known as the EPRG framework.

Etnocentric Orientation

A person who assumes that his or her home country is superior to the rest of the world is said to have an ethnocentric orientation. Ethnocentrism is sometimes associated with attitudes of national arrogance or assumptions of national superiority; it can also manifest itself as indifference to marketing opportunities outside the home country. Company personnel with an ethnocentric orientation see only similarities in markets and assume that products and practices that succeed in the home country will be successful anywhere. At some companies, the ethnocentric orientation means that opportunities outside the home country are largely ignored. Such companies are sometimes called domestic companies. Ethnocentric companies that conduct business outside the home country can be described as international companies; they adhere to the notion that the products that succeed in the home country are superior. This point of view leads to a standardized or extension approach to marketing based on the premise that products can be sold everywhere without adaptation.

As the following examples illustrate, an ethnocentric orientation can take a variety of forms:

- Nissan’s earliest exports were cars and trucks that had been designed for mild Japanese winters; the vehicles were difficult to start in many parts of the United States during the cold winter months. In northern Japan, many car owners would put blankets over the hoods of their cars. Nissan’s assumption was that Americans would do the same thing. As a Nissan spokesman said, “We tried for a long time to design cars in Japan and shove them down the American consumer’s throat. That didn’t work very well.”

- Until the 1980s, Eli Lilly and Company operated as an ethnocentric company: Activity outside the United States was tightly controlled by headquarters, and the focus was on selling products originally developed for the U.S. market.

- For many years, executives at California’s Robert Mondavi Corporation operated the company as an ethnocentric international entity. As former CEO Michael Mondavi explained, “Robert Mondavi was a local winery that thought locally, grew locally, produced locally, and sold globally. . . . To be a truly global company, I believe it’s imperative to grow and produce great wines in the world in the best wine-growing regions of the world, regardless of the country or the borders.”

- The cell phone divisions of Toshiba, Sharp, and other Japanese companies prospered by focusing on the domestic market. When handset sales in Japan slowed a few years ago, the Japanese companies realized that Nokia, Motorola, and Samsung already dominated key world markets. Atsutoshi Nishida, president of Toshiba, noted, “We were thinking only about Japan. We really missed our chance.”

In the ethnocentric international company, foreign operations or markets are typically viewed as being secondary or subordinate to domestic ones. (We are using the term domestic to mean the country in which a company is headquartered.) An ethnocentric company operates under the assumption that “tried and true” headquarters’ knowledge and organizational capabilities can be applied in other parts of the world. Although this can sometimes work to a company’s advantage, valuable managerial knowledge and experience in local markets may go unnoticed. Even if customer needs or wants differ from those in the home country, those differences are ignored at headquarters.

Polycentric Orientation

The polycentric orientation is the opposite of ethnocentrism. The term polycentric describes management’s belief or assumption that each country in which a company does business is unique. This assumption lays the groundwork for each subsidiary to develop its own unique business and marketing strategies in order to succeed; the term multinational company is often used to describe such a structure. This point of view leads to a localized or adaptation approach that assumes that products must be adapted in response to different market conditions. Examples of companies with a polycentric orientation include the following:

- Until the mid-1990s, Citicorp operated on a polycentric basis. James Bailey, a former Citicorp executive, explains, “We were like a medieval state. There was the king and his court and they were in charge, right? No. It was the land barons who were in charge. The king and his court might declare this or that, but the land barons went and did their thing.” Realizing that the financial services industry was globalizing, then-CEO John Reed attempted to achieve a higher degree of integration between Citicorp’s operating units.

- Unilever, the Anglo-Dutch consumer-products company, once exhibited a polycentric orientation. For example, its Rexona deodorant brand had 30 different package designs and 48 different formulations. Advertising was also executed on a local basis. Top management has spent the last decade changing Unilever’s strategic orientation by implementing a reorganization plan that centralizes authority and reduces the power of local country managers.

Regiocentric Orientation

In a company with a regiocentric orientation, a region becomes the relevant geographic unit; management’s goal is to develop an integrated regional strategy. What does regional mean in this context? A U.S. company that focuses on the countries included in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)—namely, the United States, Canada, and Mexico—has a regiocentric orientation. Similarly, a European company that focuses its attention on Europe is regiocentric. Some companies serve markets throughout the world, but do so on a regional basis. Such a company could be viewed as a variant of the multinational model discussed previously. For decades, a regiocentric orientation prevailed at General Motors: Executives in different parts of the world— Asia-Pacific and Europe, for example—were given considerable autonomy when designing vehicles for their respective regions. Company engineers in Australia, for example, developed models for sale

in the local market. One result of this approach: A total of 270 different types of radios were being installed in GM vehicles around the world. As GM Vice Chairman Robert Lutz told an interviewer in 2004, “GM’s global product plan used to be four regional plans stapled together.”

Geocentric Orientation

A company with a geocentric orientation views the entire world as a potential market and strives to develop integrated global strategies. A company whose management has adopted a geocentric orientation is sometimes known as a global or transnational company. During the past several years, long-standing regiocentric policies at GM, such as those discussed previously, have been replaced by a geocentric approach. Among other changes, the new policy calls for engineering jobs to be assigned on a worldwide basis, with a global council based in Detroit determining the allocation of the company’s $7 billion annual product development budget. One goal of the geocentric approach: Save 40 percent in radio costs by using a total of 50 different radios. It is a positive sign that, at many companies, management realizes the need to adopt a geocentric orientation. However, the transition to new structures and organizational forms can take time to bear fruit. As new global competitors emerge on the scene, management at longestablished industry giants such as GM must face up to the challenge of organizational transformation.

Forces Affecting Global Integration and Global Marketing

The remarkable growth of the global economy over the past 65 years has been shaped by the dynamic interplay of various driving and restraining forces. During most of those decades, companies from different parts of the world in different industries achieved great success by pursuing international, multinational, or global strategies. During the 1990s, changes in the business environment presented a number of challenges to established ways of doing business. Today, despite calls for protectionism as a response to the economic crisis, global marketing continues to grow in importance. This is due to the fact that, even today, driving forces have more momentum than restraining forces. The forces affecting global integration are shown in Figure 1-1 below.

Regional economic agreements, converging market needs and wants, technology advances, pressure to cut costs, pressure to improve quality, improvements in communication and transportation technology, global economic growth, and opportunities for leverage all represent important driving forces; any industry subject to these forces is a candidate for globalization.

Multilateral Trade Agreements

A number of multilateral trade agreements have accelerated the pace of global integration. NAFTA is already expanding trade among the United States, Canada, and Mexico. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which was ratified by more than 120 nations in 1994, has created the World Trade Organization (WTO) to promote and protect free trade. In Europe, the expanding membership of the European Union is lowering boundaries to trade within the region. The creation of a single currency zone and the introduction of the euro have intra-European trade in the twenty-first century.

Converging Market Needs and Wants and the Information Revolution

A person studying markets around the world will discover cultural universals as well as differences. The common elements in human nature provide an underlying basis for the opportunity to create and serve global markets. The word create is deliberate. Most global markets do not exist in nature; marketing efforts must create them. For example, no one needs soft drinks, and yet today in some countries per capita soft drink consumption exceeds the consumption of water. Marketing has driven this change in behavior, and today the soft drink industry is a truly global one. Evidence is mounting that consumer needs and wants around the world are converging today as never before. This creates an opportunity for global marketing. Multinational companies pursuing strategies of product adaptation run the risk of falling victim to global competitors that have recognized opportunities to serve global customers. The information revolution—what some refer to as the “democratization of information”— is one reason for the trend toward convergence. The revolution is fueled by a variety of technologies, products, and services, including satellite dishes; globe-spanning TV networks such as CNN and MTV; widespread access to broadband Internet; and Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and other social media. Taken together, these communication tools mean that people in the remotest corners of the globe can compare their own lifestyles and standards of living with those in other countries. In regional markets such as Europe and Asia, the increasing overlap of advertising across national boundaries and the mobility of consumers have created opportunities for marketers to pursue pan-regional product positioning. The Internet is an even stronger driving force: When a company establishes a site on the Internet, it automatically becomes global. In addition, the Internet allows people everywhere in the world to reach out, buying and selling a virtually unlimited assortment of products and services.

Transportation and Communication Improvements

The time and cost barriers associated with distance have fallen tremendously over the past 100 years. The jet airplane revolutionized communication by making it possible for people to travel around the world in less than 48 hours. Tourism enables people from many countries to see and experience the newest products sold abroad. In 1970, 75 million passengers traveled internationally; according to figures compiled by the International Air Transport Association, that figure increased to nearly 980 million passengers in 2011. One essential characteristic of the effective global business is face-to-face communication among employees and between the company and its customers. Modern jet travel made such communication feasible. Today’s information technology allows airline alliance partners such as United and Lufthansa to sell seats on each other’s flights, thereby making it easier for travelers to get from point to point. Meanwhile, the cost of international telephone calls has fallen dramatically over the past several decades. That fact, plus the advent of new communication technologies, such as e-mail, fax, video teleconferencing, Wi-Fi, and broadband Internet, means that managers, executives, and customers can link up electronically from virtually any part of the world without traveling at all. A similar revolution has occurred in transportation technology. The costs associated with physical distribution, both in terms of money and time, have been greatly reduced as well. The per-unit cost of shipping automobiles from Japan and Korea to the United States by specially designed auto-transport ships is less than the cost of overland shipping from Detroit to either U.S. coast. Another key innovation has been increased utilization of 20- and 40-foot metal containers that can be transferred from trucks to railroad cars to ships.

Product Development Costs

The pressure for globalization is intense when new products require major investments and long periods of development time. The pharmaceutical industry provides a striking illustration of this driving force. According to the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers Association, the cost of developing a new drug in 1976 was $54 million. Today, the process of developing a new drug and securing regulatory approval to market it can take 14 years; the average total cost of bringing a

new drug to market is estimated to exceed $400 million.45 Such costs must be recovered in the global marketplace, because no single national market is likely to be large enough to support investments of this size. Thus, Pfizer, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi-Aventis, and other leading pharmaceutical companies have little choice but to engage in global marketing. As noted earlier, however, global marketing does not necessarily mean operating everywhere; in the pharmaceutical industry, for example, seven countries account for 75 percent of sales. As shown in Table 1-5, demand for pharmaceuticals in Asia is expected to exhibit doubledigit growth in the next few years. In an effort to tap that opportunity and to reduce development costs, Novartis and its rivals are establishing research and development centers in China.

Quality

Global marketing strategies can generate greater revenue and greater operating margins, which, in turn, support design and manufacturing quality. A global and a domestic company may each spend 5 percent of sales on R&D, but the global company may have many times the total revenue of the domestic because it serves the world market. It is easy to understand how John Deere, Nissan, Matsushita, Caterpillar, and other global companies have achieved worldclass quality (see Exhibit 1-8). Global companies “raise the bar” for all competitors in an industry. When a global company establishes a benchmark in quality, competitors must quickly make their own improvements and come up to par. For example, the U.S. auto manufacturers have seen their market share erode over the past four decades as Japanese manufacturers built reputations for quality and durability. Despite making great strides in quality, Detroit now faces a new threat: Sales, revenues, and profits have plunged in the wake of the economic crisis. Even before the crisis, the Japanese had invested heavily in hybrid vehicles that are increasingly popular with eco-conscious drivers. The runaway success of the Toyota Prius is a case in point.

World Economic Trends

Prior to the global economic crisis that began in 2008, economic growth had been a driving force in the expansion of the international economy and the growth of global marketing for three reasons. First, economic growth in key developing countries creates market opportunities that provide a major incentive for companies to expand globally. Thanks to rising per capita incomes in India, China, and elsewhere, the growing ranks of middle-class consumers have more money to spend than in the past. At the same time, slow growth in industrialized countries has compelled management to look abroad for opportunities in nations or regions with high rates of growth.

Second, economic growth has reduced resistance that might otherwise have developed in response to the entry of foreign firms into domestic economies. When a country such as China is experiencing rapid economic growth, policymakers are likely to look more favorably on outsiders. A growing country means growing markets; there is often plenty of opportunity for everyone. It is possible for a “foreign” company to enter a domestic economy and establish itself without threatening the existence of local firms. The latter can ultimately be strengthened by the new competitive environment. Without economic growth, however, global enterprises may take business away from domestic ones. Domestic businesses are more likely to seek governmental intervention to protect their local positions if markets are not growing. Predictably, the current economic crisis creates new pressure by policymakers in emerging markets to protect domestic markets. The worldwide movement toward free markets, deregulation, and privatization is a third driving force. The trend toward privatization is opening up formerly closed markets; tremendous opportunities are being created as a result.

Leverage

A global company possesses the unique opportunity to develop leverage. In the context of global marketing, leverage means some type of advantage that a company enjoys by virtue of the fact that it has experience in more than one country. Leverage allows a company to conserve resources when pursuing opportunities in new geographical markets. In other words, leverage enables a company to expend less time, less effort, or less money. Four important types of leverage are experience transfers, scale economies, resource utilization, and global strategy.

Restraining Forces

Despite the impact of the driving forces identified previously, several restraining forces may slow a company’s efforts to engage in global marketing. In addition to the market differences discussed earlier, important restraining forces include management myopia, organizational culture, national controls, and opposition to globalization. As we have noted, however, in today’s world the driving forces predominate over the restraining forces. That is why the importance of global marketing is steadily growing.

MANAGEMENT MYOPIA AND ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE

In many cases, management simply ignores opportunities to pursue global marketing. A company that is “nearsighted” and ethnocentric will not expand geographically. Myopia is also a recipe for market disaster if headquarters attempts to dictate when it should listen. Global marketing does not work without a strong local team that can provide information about local market conditions. Executives at Parker Pen once attempted to implement a top-down marketing strategy that ignored experience gained by local market representatives. Costly market failures resulted in Parker’s buyout by managers of the former UK subsidiary. Eventually, the Gillette Company acquired Parker. In companies where subsidiary management “knows it all,” there is no room for vision from the top. In companies where headquarters management is all-knowing, there is no room for local initiative or an in-depth knowledge of local needs and conditions. Executives and managers at successful global companies have learned how to integrate global vision and perspective with local market initiative and input. A striking theme emerged during interviews conducted by one of the authors with executives of successful global companies. That theme was the respect for local initiative and input by headquarters executives, and the corresponding respect for headquarters’ vision by local executives.

NATIONAL CONTROLS

Every country protects the commercial interests of local enterprises by maintaining control over market access and entry into both low- and high-tech industries. Such control ranges from a monopoly controlling access to tobacco markets to national government control of broadcast, equipment, and data transmission markets. Today, tariff barriers have been largely removed in the high-income countries, thanks to the WTO, GATT, NAFTA, and other economic agreements. However, nontariff barriers (NTBs) are still very much in evidence. NTBs are nonmonetary restrictions on cross-border trade, such as the proposed “Buy American” provision in Washington’s economic stimulus package, food safety rules, and other bureaucratic obstacles. NTBs have the potential to make it difficult for companies to gain access to some individual country and regional markets.

OPPOSITION TO GLOBALIZATION

To many people around the world, globalization and global marketing represent a threat. The term globaphobia is sometimes used to describe an attitude of hostility toward trade agreements, global brands, or company policies that appear to result in hardship for some individuals or countries while benefiting others. Globaphobia manifests itself in various ways, including protests or violence directed at policymakers or well-known global companies (see Exhibit 1-9). Opponents of globalization include labor unions, college and university students, national and international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and others. Shock Doctrine author Naomi Klein has been an especially outspoken critic of globalization. In the United States, some people believe that globalization has depressed the wages of American workers and resulted in the loss of both blue- and white-collar jobs. Protectionist sentiment has increased in the wake of the ongoing economic crisis. In many developing countries, there is a growing suspicion that the world’s advanced countries—starting with the United States—are reaping most of the rewards of free trade. As an unemployed miner in Bolivia put it, “Globalization is just another name for submission and domination. We’ve had to live with that here for 500 years and now we want to be our own masters.”